The following story is from the National Compendium of 4-H Promotion and Visibility on the National 4-H History website at

http://4-HHistoryPreservation.com/History/4-H_Promotion/

There are several historical references to Will Otwell’s corn-growing boys in Illinois and beyond in the early history of Corn Clubs in the US; the story of Otwell’s creativity from 1904 is definitely a noteworthy story worth repeating.

Will Otwell was a simple, local nurseryman in Macoupin County, Illinois. He was president of the county Farmer’s Institute which had sponsored an annual county corn contest for farm boys for two or three years, each year getting a bit more successful. In 1903 Illinois Governor Richard Yates (over Otwell’s protest) gave him the responsibility of creating an exhibit representing Illinois at the great 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exhibition in St. Louis. The prospect appalled the farm-bred man from Carlinville. He knew that famed artists would create beautiful displays for other states. What could he do to match them?

Then he struck upon the idea of holding a boys’ corn contest, this time state-wide. Otwell extended the contest to include 50,000 entrants. In the fall of 1903, Otwell and his associates in Carlinville were busy opening packages of 10-ear entries of corn, drying them out, and repacking them for shipment to the Agricultural Palace at St. Louis. They sent down the best 1,250 samples from the contestants along with 600 photographs of the young farmers. This made up the bulk of the exhibit.

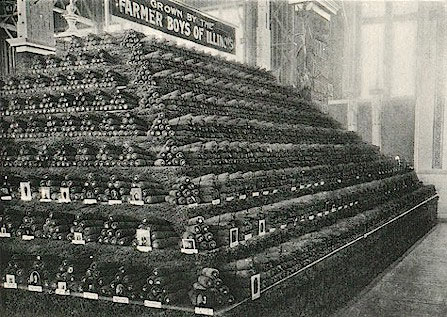

Exhibition visitors came upon the sight of two huge pyramids of corn – one of yellow corn and the other of white – arranged neatly in 10-ear samples. Above the pyramids were signs reading “Grown by the Farmer Boys of Illinois!” and “8,000 Farm Boys in Contest.” The fact that hundreds of samples were adorned with the pictures of the boys who grew them added the personal touch. The result: the Illinois corn display literally stole the show from the other states.

When newspapermen at the World’s Fair learned that each morning Will Otwell was getting approximately a bushel basket full of mail from his youthful contestants, they literally overwhelmed him for stories. The newspapers and magazines from around the country carried about 2,000 special articles about the pyramid of corn from Illinois. The display received so much attention that Otwell received offers from foreign countries to stage similar contests there.

Always “raising the bar,” in 1905 Otwell invited farm youth from anywhere in the country to come to Carlinville for a national roundup of corn growing contestants in his home town.